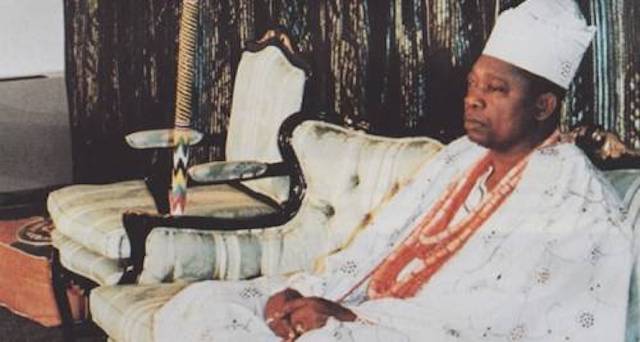

On the 20th anniversary of MKO Abiola’s death on 7 July, Dr. Yemi Ogunbiyi, a former associate of MKO and pro-chancellor of Obafemi Awolowo University reproduces a portrait first published in 1993, of the man who was denied from claiming the presidential mandate given him by Nigerians in the election of 12 June, 1993.

Following the honour bestowed on MKO Abiola by President Buhari and the re-focused attention on Abiola’s legacy, my daughter Oreoluwa, who, by the way, read Politics and Philosophy at Cambridge and was only one year old when MKO was killed, called me to find out more about him.

Here is how she put it: ‘Dad, I know all about June 12 and how Chief Abiola was denied the presidency and later died in prison; but what kind of man was he?

Oreoluwa’s question set me thinking and it suddenly dawned on me that many younger Nigerians, certainly the twenty-‘somethings’ and even thirty-year olds may just have only a vague memory of MKO Abiola or none at all, let alone knowing who the ‘real’ MKO Abiola was!

Because of Oreoluwa and others of her age, I have decided to reproduce in full, the first chapter of the Book, Legend of our Time: The Thoughts of MKO Abiola, which is a published collection of Abiola’s key Speeches and Lectures, edited by Dr. Chidi Amuta and myself.

The book, which was published on the eve of his presidential campaigns, predates the June 12 saga.

Obviously, he will now for ever be remembered for his June 12 victory and as an embodiment of our democratic ideals. But he was more than June 12!

Indeed, June 12 was the culmination of a tremendously remarkable life.

In some ways, there was none like him and there probably would be none quite like him again.

He was, among other things, a man of prodigious intellectual talent, a true legend of our time. Just months before his death, I visited him in prison. Although tired and suffering from a lower back pain, he was, even in his dismal conditions, his old self. He oscillated between anger, anxiety, frustration and even optimism, but not bitterness.

Then, when a prominent, Egba Chief (now, late), came in to see him, apparently carrying with him some message from the Council of Islamic Affairs, in what seemed to be another of several previous visits, MKO flared up and his defiant self resurfaced! Then, after the Chief took leave of us, he turned to me and asked me how I thought he had done! I gave him the thumbs up!! Instantly, the young security guard who had listened in on our entire discussion told me it was time for me to leave. I never saw MKO again.

Again, there are seeming contradictions here. But what is a great man if not a bundle of opposites, contrasts and even contradictions? Isn’t it the rich admixture of warmly human virtues and failings that change our admiration into love, especially too in our assessment of great men? And in the case of Bashorun Abiola, given his sheer vitality and energy, the contrast are sometimes even more dramatic and startling.

So, in reproducing this lengthy piece, which was written in late 1992 and titled “Behind the Legend,” I have felt no need to change, embellish or delete any details. The man I wrote about then, remained the man I saw in prison, months before his death in 1998, determined, defiant, uncowed and unbowed.

Because of this man, there is both cause for hope and certainty that the agony and protests of those who suffer injustice shall give way to peace and human dignity…. The enemies which imperil the future generations to come: poverty, ignorance, disease, hunger, and racism have each seen effects of the valiant work of Chief Abiola. Through him and others like him, never again will freedom rest in the domain of the few.

On Saturday, November 2, 1991, I had the privilege of flying with Bashorun M.K.O. Abiola in his private jet to Kafanchan to attend the turbaning of Alhaji Aliyu Muhammad as the Wazirin Jema’a. At the Abuja airport we changed aircraft and took a helicopter which took us on the final lap of our journey into Kafanchan. After hovering above the scene of the ceremony for few minutes, our pilot finally located a clearing for landing. The moment the occupant of the helicopter was spotted, the stampede began. The drummers were beside themselves. The trumpeters outdid each other.

Singing and dancing groups added to the confusion by raising more harmattan dust. All these were meant, of course, to acknowledge the arrival of Chief Abiola. Even uniformed officers who had been designated to keep some order watched helplessly, in an admixture of bewilderment, admiration and confusion. Considering that this was happening in Kafanchan, away from the presumed heartland of Abiola’s socio-cultural stronghold, I was quite surprised. The massive attention that greeted Chief Abiola’s arrival was remarkable. I stood back, almost detached from it all, to see if any other arrival would attract such attention. Surprisingly, none did.

Viewed from any point of view, Bashorun Abiola has become something of a national institution. By any standard, he is a phenomenon. Something about him, perhaps, his unique expansiveness of spirit and stupendous generosity, embodied in his enormous wealth, have combined to embed him in our national consciousness in a peculiarly Nigerian way.

From the point when he first entered the full glare of national limelight in 1975, with the award of the International Telephones and Telecommuncations (ITT) Contingency Switching contract, all kinds of legendary tales have developed and gained currency about him. There is, perhaps, no other private Nigerian citizen, who has the distinction of being recognised anywhere in the country by his initials alone. In many of Nigeria’s villages, it is certainly probable that the initials M.K.O. will elicit a spontaneous response from Nigerians who may never set eyes on Chief Abiola.

Although a private citizen, Bashorun Abiola is sometimes accorded all the courtesies of a visiting head of state abroad, especially in Africa and from the black diaspora. Indeed, at the inauguration ceremony of President Bill Clinton, he received courtesies reserved for a head of government by virtue of the prominence of his seating position, inches away from the main event. More than anyone else, he has helped tremendously in the election of more African-American Congressmen and women in the United States of America, through direct financial assistance, deriving no gains in return, save the joy of seeing African peoples of the diaspora take greater control of their own destinies in their country of birth. His direct assistance to Yoweri Museveni in his liberation struggles in Uganda is too well known to be recounted here. It is sufficient merely to recall that he gave massive financial assistance to that cause. He has travelled extensively around the world on his own, addressing diverse groups of audiences on a whole range of subjects, from Pan-Africanism to Reparations, Technology, Sports, Education, Racism, African political theory, African folklore, Business, the Environment, and “our connectedness as African peoples to a wider flow of world history”, – again, asking for nothing in return.

Although a private citizen, Bashorun Abiola is sometimes accorded all the courtesies of a visiting head of state abroad, especially in Africa and from the black diaspora. Indeed, at the inauguration ceremony of President Bill Clinton, he received courtesies reserved for a head of government by virtue of the prominence of his seating position, inches away from the main event.

At last count, he had been conferred with 197 traditional titles by some 68 different communities in Nigeria. Bashorun Abiola had been honoured by scores of educational institutions, worldwide, the last one being an honorary degree from the University of Makerere, Uganda. Since 1972, his financial assistance has led to the construction of some 63 secondary schools, 121 mosques, 41 libraries, and 21 water projects in 24 states of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. He is, to date, the grand patron of some 149 societies or associations in Nigeria alone, that is, not counting his affiliation with scores of professional associations at home and abroad. During the conferment of the award of the “Order of Merit of Gold”, Africa’s highest award for Football in Dakar, Senegal, in January 1992, it was revealed that no other African, dead or alive, had made as many “quantifiable contributions” as he had made to the development of sports in Africa.

By any standard, these are phenomenal achievements for a single being in one full life time, let alone one that has spanned a mere fifty five years. Yet, we may not quite know him as he really is. There is the danger, ever so real, that he could become the wrong sort of myth for the wrong sort of reasons.

Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola, who was born on August 24, 1937 in the Gbagura quarters of Abeokuta, was a descendant of Agbon who led the Gbagura warriors into Abeokuta in 1930. Traditionally, Gbaguras are warriors and had taken up settlement in the outer boundaries of Abeokuta, where they conveniently defended the city from outside invasions. If you accept Samuel Johnson’s explanations in his seminal work, The History of the Yorubas, then the Gbaguras were closest to Oyos in mannerisms and perhaps, by implication, the most cunning of the Egbas! Although, the view that young Abiola was born into abject poverty seems to have percolated somewhat, his father, Alhaji Alao Salawu Adenekan Abiola was a small time produce buyer in Ikire even before Moshood was born. And although Moshood was his twenty-third child, he was the first to survive, the first twenty-two dying either at birth or before attaining the age of one; hence the name Kashimawo, indicating the uncertainty that was felt even about his own survival.

The homestead in Adatan into which he was born was the subject of litigation at his birth. Evidently, when Moshood Abiola’s grandfather passed away, his father and his aunt raised a loan to help fund the funeral ceremonies. The understanding was that Moshood Abiola’s aunt would provide service to the money lender in lieu of the money borrowed under the traditional system of Iwofa. Much later, when she decided to get married and lead her normal life, an arrangement that was wholly acceptable under the Iwofa system, the money lender refused and decided to appropriate the Abiola family house. The ownership of that family house was in dispute when Moshood Abiola was born.

Many years after, Bashorun Abiola came under pressure from the larger Abiola family to seek redress in a modern-day court of law and regain the family house. He refused and opted instead to buy a new property elsewhere for the family. This incident left lasting impressions on Moshood Abiola as a child. The fact that a supposedly “free” person could be denied the right of marriage under an “obnoxious” custom was, in Abiola’s own words, “something similar to slavery.” In retrospect, it makes even more sense today that the latter-day Pan-Africanist champion of Reparations for the crimes of slavery would have felt as passionately as he did, the injustice of the much abused Iwofa system. The repulsion for this kind of injustice was to characterise much of his early, and subsequent career.

For a man who was born and raised a moslem, it is significant that, apart from one long early spell of Koranic education at the Nawair-ud-Deen School in 1944, all of his pre-University education was under the watchful eyes of Baptist missionaries; Baptist Day School, (1944-1952), and Baptist Boys’ High School (1951-1956). Presumably, at this time, the best colleges in and around Abeokuta were Christian missionary schools. Apart from the near-spartan discipline of Baptist education, with its dose of Calvinism, other aspects of the Baptist faith influenced him tremendously.

For a man who was born and raised a moslem, it is significant that, apart from one long early spell of Koranic education at the Nawair-ud-Deen School in 1944, all of his pre-University education was under the watchful eyes of Baptist missionaries; Baptist Day School, (1944-1952), and Baptist Boys’ High School (1951-1956). Presumably, at this time, the best colleges in and around Abeokuta were Christian missionary schools. Apart from the near-spartan discipline of Baptist education, with its dose of Calvinism, other aspects of the Baptist faith influenced him tremendously.

The picture of a young Moshood Abiola selling fire-wood to raise money for his school fees or leading a local musical group of his own to raise extra school money was in consonance with the free-wheeling spirit of his Baptist education. When Rev. S.G. Pinnock founded Baptist Boys’ High School, Abeokuta in 1923, the precepts of hard work and individualism within the framework of a collective ideal were amply spelt out and strictly adhered to. Even the tough rugged approach to the old site at the Egunya Hill seemed designed to tell a story of hard work in itself! That Baptist Boys’ High School has on its roll of old boys some of the highest achievers in our country is partly a testimony to the ideals of hard work, dedication and service which the institution stood for over the years: Former President Olusegun Obasanjo, Professor Ojetunji Aboyade, Engineer Yemi Fabunmi, Mr Justice Obadina, Engineer Ayinla Somoye, Professor Adeoye Lambo, Chief Olawale Ige, former Communication Minister, veteran journalist, Tunji Oseni, to mention just a few.

As Bashorun Abiola himself recalled later, “it was the best school in the world… Education at that school was what we called education-plus.” Against many odds, Moshood Abiola plodded on. Not even a bad stammer as a child deterred him.

What was to become a lifelong love with journalism started with his editorship of the school magazine, The Trumpeter, in his final year. Olusegun Obasanjo was deputy editor. Although a day student, he took more than a passing interest in sporting activities. It is also just probable that the seeds of what was to blossom into a lifelong romance with sports were sewn during these years. It is also important to point out that the social setting in which his adolescent character matured was the Abeokuta of the World War II years and a little after. The period just before 1945 and after, were interesting years to be growing up in Abeokuta. The nature of the political, social and cultural ferment that was taking place in Abeokuta at the end of World War II is hardly duplicated anywhere else in Nigerian history. Abeokuta was one huge flurry of activity. There was, for instance, the political activism of the Women’s Movement led by the irrepressible Mrs Ransome-Kuti, alias Beere; there was the presence of Nigerian and foreign troops in several locations in Abeokuta; there also the activities of several Christian groups with their experimental forms of African worship. There was, opposed to this latter group, the Egba Ogboni, that symbol of the ancient repository of Egba history, regal in the splendour of their colourful round-rimmed hats, shawls, fans and all, and fearsome in the enormity of their intriguing prescience. Every school boy growing up in and around Abeokuta at that time had to have known of these developments and activities.

Moshood Abiola must have come to manhood believing that such essential ideals as freedom, justice and fair play were quite desirable and attainable. A rebellious spirit typified those years. Many years after, Abiola was to recall: “You see, if I hadn’t rebelled, I would have been virtually a nobody by now. There was no way I could have paid my school fees. What is rebellion? Rebellion is looking for the most unusual way out of a very sticky point.” And find a way, he did.

After brief working stints at the then Barclays Bank (now Union Bank), Ibadan, and the Western Regional Finance Corporation, a western Nigerian Government scholarship took him to Glasgow University in Scotland, in 1961, to study Management Accountancy. The Glasgow years are important for us now, not only because he distinguished himself academically (first prizes in Political Economy, Commercial Law and Management Accountancy) but essentially because it also marked, ironically, the beginning of his serious encounter with Pan-Africanism. Apart from active participation in endless debates on the best options open to African peoples, Abiola undertook a trip, in the company of other west African students based in Glasgow, to the newly independent state of Ghana, in 1963, to brainstorm with Kwame Nkrumah, supposedly, on a programme of action for African and the Black race.

Although he came back to Scotland from the Accra trip disillusioned because Dr Nkrumah was far too impatient to give adequate attention to a group of young idealistic African students, Abiola’s mind seemed made up now about Pan-Africanism. Many of the events that were to take centre stage in his life in subsequent years were the results of several encounters with other African students at Glasgow between 1961 and 1965.

Glasgow also looms large in his life because there he got married to his first wife, the late Alhaja Simbiat Abiola, and there they had their first two children, Kola and Deji. Literally weeks after his final examinations in Glasgow, he returned home in March 1966 to a country torn apart by an imminent civil war.

His first job was with the University of Lagos Teaching Hospital and subsequently he worked for Pfizer. In August of 1968, he joined the International Telephones and Telecommunications (ITT) as its Finance Controller. That decision was to change the course of his life. Since this phase of Abiola’s life has been over-romanticised in tales that take on an air of folkloric myth, the facts of the matter should be restated for the record.

Fortunately, Chief Abiola has been forthcoming with details in this regard. While admitting to support from a myriad of people, both at home and abroad, in his rise to financial prominence, he identifies the ITT link as the source of his first breakthrough. Basically what happened was that he used his connections with friends in government, among them the late General Murtala Muhammed, to win key business concessions for ITT. But instead of settling for the usual fixed salary, he opted for shares of the business.

Let us listen to Abiola tell the story himself:

“I proceeded immediately to London with the cheque to report on the affairs in the office and I insisted that I could only carry on in the company if I became the Managing Director and at the same time be given no less than 50 per cent of the shareholding of the business. The Managing Director aspect of the request was granted immediately, but the shareholding part of it, I was told required top policy consideration which would be resolved within six months… The bottom line, in fact, was that I was requesting that at the determination of the profit for any year, half of that profit should be left behind in recognition of my contributions for making the whole profit. No more, no less.

“Eventually, ITT acceded. Abiola ended up controlling a bulk of the business in Nigeria. Barely nine months after he joined ITT as Controller, he rose to become Managing Director. That year – 1969 – his salary jumped from £9,400 per annum to £114,380 per annum, a phenomenal rise of over 1,000 per cent! By December 1970, he became Chairman and Chief Executive of ITT (Nigeria) Limited.”

The rest, of course, is now history.

Not surprisingly, this period coincides with his sponsorship of sporting activities on a large scale and his first wave of support for philanthropic activities. His entry into mainstream Nigerian politics seemed a matter of time. Following his nomination into the Constituent Assembly in 1977 and the numerous contact opportunities derived from the assignment, it did not come as a surprise when he opted for partisan politics.

The National Party of Nigeria (NPN) seemed the natural party to join at the time and he did just that, emerging as a member of the party’s National Executive and its leader in Ogun State. Some people have argued that Bashorun Abiola’s impact on the political scene was diminished by the fact that he joined the “wrong” party in 1978, and that he might have made a greater impact had he belonged to the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) which was then headed by Chief Obafemi Awolowo. Such people argue further that he opted for the NPN rather than the UPN as a protest over the personal attacks on him by the then leadership of the UPN. These views may be correct, but only partially. That position ignored the evidence of M.K.O. Abiola’s past, a past which was not consistent with joining the UPN, at least, as constituted at that time. A former member of the Zikist Movement as a much younger man, he had embraced Pan-Africanism passionately. And, as we argued earlier, he always had a rebelliously democratic streak to him, which compelled him to gravitate to less conventional settings or associations. This may well explain why he could not survive within the UPN, with its seemingly strict hierarchical set-up.

Indeed, it might be pertinent here to consider the circumstances which led to his resignation from the NPN. At the core of that decision was a yearning for a genuinely democratic arrangement, one which would ensure that members of the party were equal partners of the association. The text of his resignation letter of 14th July, 1982, a document of historic value in its own right, deserves to be quoted here in full:

Resignation From NPN

“Having had consultations with members of my family and after a deep reflection on the state of affairs in the country, I hereby tender my letter of resignation from the National Party of Nigeria as well as my membership of the National Executive Committee of the party. I am of the firm belief that my conscience can no longer tolerate the way and manner in which the administration is directing the country. Corruption, nepotism and tribalism have now become the order of the day. Furthermore, I can no longer interact in a party where the right to contest for one’s political right is premised on tribal considerations, an antithesis of what true democracy stands for. I sincerely hope that my resignation is accepted in good faith”.

Conversely, this letter may contain some secret of why, in 1992, he opted for the Social Democratic Party (SDP) rather than the National Republican Convention (NRC).

Again, those who see opportunism in that decision may have missed the point entirely. To be sure, ideologically, Bashorun Abiola ought to be more right of centre, than left of it. But that is only half the story, for as will be shown presently, Bashorun Abiola is a lot more. The issues are not quite as clear-cut as they may seem from the outside. For instance, Bashorun Abiola is, predictably, a fiscal conservative. This means that on economic matters, he tends more to be right of centre. This, one suspects, is what that radical former Governor of Kaduna State, Balarabe Musa means when he described Abiola as “a liberal national capitalist.” Due partly to his background and temperament, he grew to have a social conscience, the kind that one does not often encounter in the very wealthy. Consider, for instance, his anti-Thatcherite position on the Nigerian Economy, a view that runs counter to the cut-in-money-supply doctrines of Milton Friedman, the economic guru of the far right. Speaking at a New Nigerian newspaper forum in April of 1985, Abiola had called on the government of the day to exercise caution in forcing down a Thatcherite economic agenda on an already over-burdened population

Like all successful business managers, he goes for the best when he hires: well-trained, and therefore, adequately remunerated subordinates. Neither is he afraid to delegate functions. Invariably, an unusually close rapport develops between him and his staff. When the editors of his newspaper were detained and later put on trial as happened to the late Dele Giwa and Ray Ekpu, he made it a point to attend the trials. When another editor became President of the Nigerian Union of Journalists, he hosted him to a lavish party. But when the same staff members fall out of line and appear to forget who is boss, he applies, even if hesitantly, the big stick, and fires them.

Again, there are seeming contradictions here. But what is a great man if not a bundle of opposites, contrasts and even contradictions? Isn’t it the rich admixture of warmly human virtues and failings that change our admiration into love, especially too in our assessment of great men? And in the case of Bashorun Abiola, given his sheer vitality and energy, the contrast are sometimes even more dramatic and startling.

Although endowed with all the patient instincts of a successful, shrewd businessman, he can be devastatingly abrupt. And yet, even the abruptness is usually not informed by a personal animus because he has the most complete freedom from cruelty and malice. A quickness to forgive ensures that the next minute he is back to his usual self. Although never a man to play down his own worth, he also, sometimes, displays profound humility and modesty, propelled, presumably, by the dictum that a man is never more on trial than in a moment of excessive good fortune, especially too, where such good fortune is seen as Allah’s handiwork. Because of his breathtaking schedule, he cuts the deceptive image from the outside of a man who is not quite as organised as he should be. Yet, properly observed, he is one of the most organised of men. His ability to keep up with his extensive schedules astounds close observers.

Shortly after he was elected President of the Newspapers’ Proprietors Association of Nigeria (NPAN), some members expressed doubts that he would ever find time for the association. Not only did he find time to convene regular meetings, he surprised members with his inside knowledge of current goings-on in branches of the association.

Consider also the fact that large as his family is, he keeps track of all his 63 children, remembering each child’s birthday and those of his own personal friends. I recall how a couple of years ago, I was woken up at six in the morning on my birthday by Bashorun Abiola, singing a “Happy Birthday” song at the other end of the telephone.

Without question, we are dealing here with a unique human character. Some people are self-effacing by nature, choosing to exploit their elegance as a disguise and always preferring the background to the foreground. Such people usually opt to embellish their strength with an air of indolent detachment. By contrast, there are those who wish to stand out loudly, not necessarily as heroes but as leaders. Tough, ebullient and bold, such people seem cut for the rough-and-tumble of leadership.

M.K.O. Abiola belongs to this latter group. As he is known to say frequently, “You cannot swim in water without getting wet. If you do not wish to get wet, then don’t enter the pool at all!” Abiola is clearly the least brittle of men, the least contrived of personalities. He is, sometimes, to his own detriment, incapable of maintaining a smooth façade for long. Sooner or later, the lid pops open and the real character streams out, forthright, spontaneous, outgoing, combative, tremendously whole-hearted and with a little touch of mischievousness to him! He has a ready wit, enriched even more by his deep knowledge of Yoruba folklore. Hardly ever known to have been caught unawares, he is one man who literally thinks on his feet. There is also to him an indulgent self-enjoyment. And yet, this is part of the problem. Because his joker-ish persona sometimes persists, it conceals fibre and character unsuspected by the casual observer. He hides a tremendous thrust and energy under a deceptive surface of charm. His ability to move from one event or social function to another within the country is virtually unsurpassed. It is unlikely that any other Nigerian covers as much ground in foreign or local travels as he does.

Bashorun Abiola is also unique in his absolute bedrock convictions. Once he has settled on a cause of action, that cause becomes a holy mission, a crusade. And in this regard, his Reparations cause comes readily to mind. Once he was convinced about the case for Reparations, armed by every available literature on the subject, he embarked on a lecture tour of Africa and the diaspora. Subsequently, an international conference on reparations was organised in Lagos to which key African and African-American leaders were invited. That conference laid the groundwork for what was to become the Organisation of Africa Unity’s (OAU) Eminent Persons Group on Reparations. The Group, made up of some of the finest academics in Africa and the diaspora, among them Professor Ade Ajayi, Professor Ali Mazrui and Ambassador Dudley Thompson of Jamaica, is charged with the task of documenting all available evidence on the subject, with the aim of presenting a powerful case before the United Nations. It is significant to note that Bashorun Abiola donated handsomely towards a fund set aside by the OAU for the Reparations struggle. In Abiola’s scheme of things, the

Reparations debate and the fight for the political and economic freedom of African peoples are identical struggles. For him, the massive support he has given and continues to give African-American causes in the United States, either by way of financial support to African-American politicians or even to African causes on the continent, as in the case of Uganda and Museveni, are variations of the same global struggle. As in the Reparations struggle, the fundamental objective of the support for African/American causes is the restoration of the dignity of the African. There is no greater recognition of the unity of this struggle than the tribute paid Bashorun Abiola by the members of the Congressional Black Caucus of the United States Congress.

Read more at:www.vanguardngr.com