After the Boko Haram insurgency began in northeast Nigeria in 2009, thousands of people started fleeing the region to other parts of the country, including to my home city of Calabar in southern Nigeria.

Many of these survivors were children who had lost their parents during the war. Rather than continuing their education, they were transported to Calabar by modern-day slave owners who found work for them as housekeepers and gatemen, and received pay on their behalf.

I had never been to the northeast of my country, but I was so touched by their stories – including of rape, torture and intimidation by Boko Haram militants – I decided to move there to become a human rights educator and children’s rights advocate.

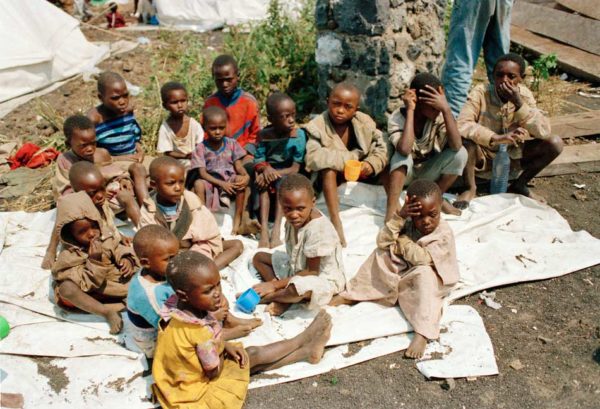

I relocated to Maiduguri, the capital of Nigeria’s northeastern Borno state, and moved around the internally displaced persons’ (IDP) camps in the region supporting displaced children so they could enrol in primary school.

One day in 2013, a 13-year-old named Falmata came up to me in an IDP camp in Maiduguri and asked: “Can you tell the whole world that I lost my parents, my siblings and my home, and can’t return to school?”

At that time, I saw Falmata’s situation primarily as a concern for the Nigerian government and human rights organizations. I was constantly writing about the situation in letters and proposals to funders and policymakers, but journalism was far from my mind.

One evening that August, I came back to check on Falmata and discovered that she had sneaked out of the camp the previous day. She had left a note behind saying that she was “going to Niger” with a woman she met a day before who “promised me a job in a farm.”

I was devastated with sadness and guilt. I thought maybe Falmata could have been saved if I had just documented and shared her story, at least on social media.

Eventually, I did write about Falmata and shared her story on Facebook. It was the beginning of my foray into journalism. In 2015, I started writing other stories about children in communities targeted by Boko Haram, and soon newspaper editors both in Nigeria and abroad began to seek articles from me.

I found that I was able to solve more problems by being both a human rights educator and a journalist. I was not only able to provide children with knowledge about human rights, but also educate the world about the rights violations happening to these children.

I first met Sarah, a 17-year-old girl who was abducted by Boko Haram militants from her hometown of Bama after she fled captivity to an IDP camp in Madinatu, near Maiduguri. I got to know Sarah while providing psychosocial support to her and other children in the camp.

When an agent for a trafficking ring approached her in January 2017 and offered her a job in Italy, she told me she wanted to go. “I really want to go abroad and work,” she said. “I may die of hunger if I remain in this camp.”

I tried to talk Sarah out of it, and thought she had listened to my advice. But when I went to look for her the next day, she had already left for Benin City in southern Nigeria. There, she underwent an oath-taking ritual to ensure her loyalty to her trafficker before the journey through the Sahara Desert, and across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.

After Sarah left, I started investigating human trafficking out of IDP camps in northeast Nigeria.

Trafficking is a widespread phenomenon in this country. Each year, thousands of Nigerian women and children, especially those from rural areas, are taken to neighboring countries in West Africa, or to Europe, Asia and the Middle East where many are forced into involuntary domestic servitude or sexual exploitation.

Poverty plays a key role in the business. In northeast Nigeria, hundreds of thousands of people – mostly women and children – have been displaced from their homes as a result of the Boko Haram insurgency. Many find life impossible in IDP camps where there is hardly enough food to eat. Traffickers – through coercion, deception and even violence – take advantage of the situation to entice young women and children with promises of well-paid jobs.

“One woman stopped me on my way to get water from the dam [outside the Madinatu IDP camp] and asked me if I wanted to work in Niger,” 17-year-old Hadiza told me during a human rights education session in Madinatu. “I told her I couldn’t leave my sick mother behind and go to Niger.”

Covering these stories as a journalist was important. But I also wanted to start a local public education campaign about human trafficking. Up Against Trafficking officially launched in April 2018, beginning with a camp-to-camp advocacy program.

As both a journalist and a human rights educator, I started noticing patterns in the traffickers’ tactics. Many girls, like Hadiza, met traffickers on their way to fetch water outside the camp late in the evening.

In most parts of Borno state, access to clean water is scarce. Many public water supply units were affected by the attacks in the region. The few clean water tanks or boreholes that exist in IDP camps are often overcrowded. Those who can’t wait for long hours turn to dams and streams where water is often polluted.

Madinatu is so dry it resembles a desert. A tanker provided by humanitarian groups delivers water twice a day to thousands of people in the IDP camp. The camp is the size of more than 20 football fields, so many people have to trek long distances to reach the tanker. Some people who live close to a dam outside the camp prefer to fetch water from there, risking waterborne diseases and an encounter with human traffickers.

Campaigners for Up Against Trafficking have helped to provide constant clean water to the camp through an electric-powered borehole at the camp’s entrance. For us, easy access to clean water is one important way of weakening human traffickers and protecting displaced persons in Madinatu from exploitation.

We had barely kickstarted the campaign, when I got a phone call from Ahmed, a member of the local vigilante group, Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), telling me that he had just had a conversation with two girls who were preparing to leave with a woman who promised to give them jobs in Italy.

“The woman is not real,” Ahmed told the girls. “Mr. Philip (as people usually call me in Madinatu) has written about these kind of women in the past.”

Ahmed was referring to a story I had written about Sarah and other children in and around Madinatu who were either trafficked or paid people-smugglers to take them through the Sahara Desert and across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. The story went viral across Nigeria, and it caused the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons to further increase its surveillance in IDP camps.

“You’ve got to do something to stop these girls from traveling,” Ahmed said to me after he had tried in vain to make them change their minds.

I quickly moved all the reports I had written about human trafficking out of northeast Nigeria into a single Word document and sent it to Ahmed so he could give it to the girls, who fortunately had learned to read. They quickly dropped their plans to travel, and eventually joined Up Against Trafficking as advocates who inform and educate other displaced persons about the dangers of human trafficking.

“It’s better to struggle here than to be slaves abroad,” one of the girls told Ahmed.

Today in Madinatu, no voices speak louder than those of girls in the IDP camp who are determined to defeat human trafficking in the place they now call home. They deserve to be heard and given support.

Culled from News Deeply